I should have written this post about one year ago when it all started. However, as many of us teachers were, I was extremely busy trying to cope with the new reality. At first, I really thought “quarantine” would mean about 40 days at home, but here we are, eleven months later, still planning online lessons.

Back in March 2020, I was teaching at two schools: a general English course and a bilingual school, which meant two different perspectives. With my course students I had two 1 hour classes a week and with my school students I had five to six classes of 50 minutes a week. Luckily, both schools were using Google Classroom and Meet, so I had to learn how to use only one platform.

This was my context when everybody in Brazil were in “lockdown” and schools were closed for an indefinite period of time. Here, I would like to summarize both experiences because I think they were so different and it would be nice to share and remember them later on.

Teaching online at an English course

The first positive aspect of teaching in this context was having fewer students per classroom. My biggest class had only 12 students. This means that I could hear each one speaking, check pronunciation and do more error correction. I could give enough attention to each of them and better feedback to them and their parents in meetings. When there were still no breakout rooms available in Google Meet, I could create another meet and send them the link, so I still could do some group and pair work.

Another good thing was to have online platforms for all materials I was using. I didn’t waste any time scanning books or looking for extra materials. All I had to think of when planning my lessons was how to adapt some of the activities to the new context. This helped me a lot.

I would say a negative thing about teaching at a course was that my lessons had 75 minutes before, and now they only had 60 minutes. So, in addition to all technical issues the student would have every class, I didn’t have those 15 minutes and I really wish I did.

Also, there was no time for learner and teacher training. We learned new things as we went through the classes and shared our problems with our fellow teacher whenever we could. Many students were confused about how to use the apps and really how the Google Classroom worked. Some of them couldn’t even upload their activities, and some of the young learners didn’t have adult’s assistance during the lessons.

Teaching online at a bilingual school

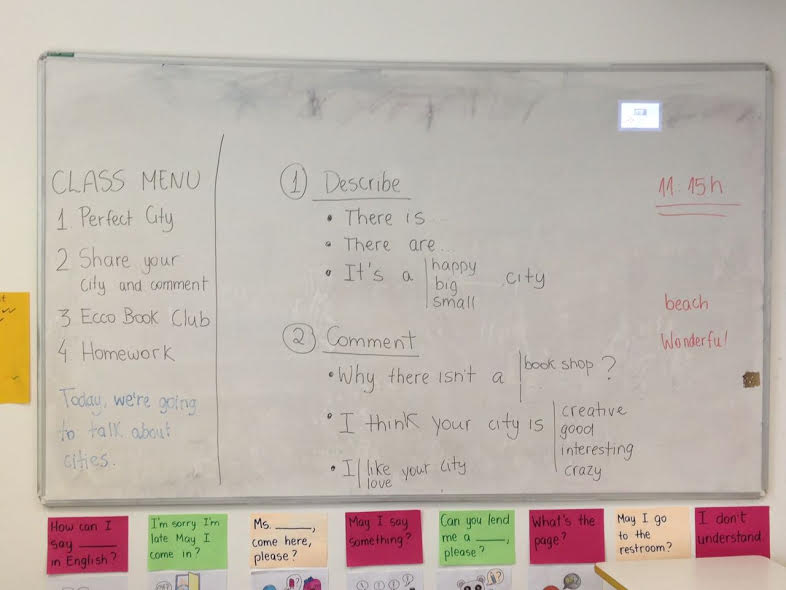

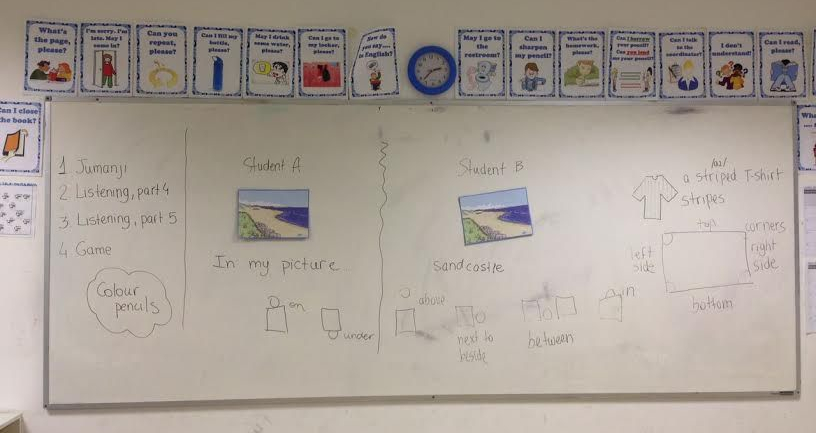

The first – and perhaps only – positive aspect of teaching online at a regular school was to have more time with the students every week. I would meet them for 5 to 6 lessons of 50 minutes each, so I could do more activities and had more time to solve any technical problems. The syllabus was cut in half, so I had time to do projects, focus on phonics and reading activities.

This also had a downside. I had to find extra materials because I couldn’t use the whole book. Also, the material we used in this school had no online resources whatsoever. I mean, zero! In 2020! Can you believe it? Anyway, it was extremely time consuming to find and adapt extra activities every week.

However, the biggest issue for me was how to deal with so many students in class at the same time. There were 25 in one class and 21 in another. Young learners tend to turn on their microphones to say the most random things in the most inconvenient times (during instructions, interrupting their peers, and so on), so this would happen a lot during one lesson.

Overall

The 2020 experience was definitely challenging. Personally, I could find many positive aspects to teaching online. The negative issues, I believe could have been less “traumatizing” if we had had time to do some learner and teacher training in advance. But how could we have foreseen what was coming? In my experience, there was little support from the coordination – it’s understandable, as they were dealing with their own problems – and very little training opportunities.